In the spring of 1925, engineer Douglas “Duggie” Larter began a lengthy recording expedition in Asia for the Gramophone Company. He started recording in June of that year in Lahore, in what is now Pakistan, and over the next two years would record all across South Asia in places like Calcutta, Delhi, Mysore, Colombo, and Karachi, and as far east as Singapore and Jakarta, recording the rough equivalent of 1,800 78s.

During those two years, he returned to Lahore multiple times for sessions. In June of 1926, while in that city, Larter did something historic: he helmed the first significant recording session of Afghan musicians and Afghan classical music. A total of 59 discs were recorded and released. A small group of musicians traveled from Kabul to Lahore for these sessions. Not all of their names are known, but the primary artist was Ustad Qasem Afghan (1878-1957), considered the father of Afghan classical music. Accompanying him was a rubab player named Qurban Ali, and additional performers who were listed on records and catalogs as the “Kabul String Band.”

Ustad Qasem Afghan appeared on 56 of those discs (except for one instrumental side by the String Band). Qurban Ali, on the other hand, appeared as a rubab soloist on just three discs (again, except for one instrumental side by the String Band), with tabla accompaniment. The track featured here is a performance in the raga Asavari, and while the recording is a bit thin (it is a late acoustic recording, made without the use of microphones), the performance is still resonating.

I’ve asked rubab player Mathieu Clavel to help explain the significance of this performance.

Mathieu:

The style of “classical” rubab (also known as Kabuli; the urban rubab, as opposed to the folk rubab of the countryside) is said by scholars to have emerged as early as the late 19th century (see the works of Prof. John Baily). The progress of instrumental music accelerated when Amir Habibullah forbid the performance of dancing girls for the men of the court, as most of the musicians’ performances relied on accompanying dance performances. This legacy of Afghan art music actually began when Amir Sher Ali Khan, Habibullah’s grandfather, invited groups of nautch dancers (court dancers) and related musicians to settle in Kabul after being entertained while on a diplomatic invitation to India in the mid-19th century. Many of today’s professional Afghan classical musicians descend from them.

As the rubab player in the group of Ustad Qassim Afghan at the royal court, and one of the very first Afghan musicians to play on air when radio first launched in the country, Qurban Ali was known as one of the best rubab players of Kabul in the first decades of the 20th century. He also fathered several noteworthy artists, one of them being the late Ustad Ghulam Dastagir Shaida, one of the most wonderful Afghan classical singers of the century.

Raag Asavari is a melody rarely if ever heard on the rubab. It is related to raag Darbari, the “sultan of ragas,” and shares with it a solemn mood. Qurban Ali is showing nicely the character of the raag, setting the mood with a few notes of shakl (the Afghan version of the Indian alap) before getting into the composition. He does incorporate the major 7th, which is out of the raag’s rules; it is however not rare to see such minor digressions in Afghan compositions for the sake of beauty.

The composition is played with the kharj (tonic) set in Rekap, the 3rd fret of the low string; a typical, historical yet beautiful feature of classical rubab, which gives room to explore the lower octave a little bit, down to the lower 6th, since the rubab does not have the extensive range of Indian classical instruments to perform the same modal material. Nowadays, classical music is quite often played with the tonic set in the 1st fret of the low string, which is sometimes called “chapa” or “gauchely” as opposed to having the tonic set in the 3rd fret, “rasta” or “straightforwardly” – while folk is originally played with the tonic in one of the open strings.

The rhythmic cycle is the 16 beats tintal, and to my opinion the composition sounds rather “Hindustani,” as in more complex, with different right hand patterns or bols within the composition, similar to sarod material heard from recordings of this time (the sarod having evolved from the rubab). And what a sweet and impressive composition, which two parts he is playing with subtle variations: the asthai, main and opening theme, and the antara, a second melody that goes higher in range. He plays the latter starting at 0:30, comes back to the asthai at 0:50, and again to the antara at 1:30 before moving to a bridge till 1:45 and then a second composition (another Hindustani gat rather than a typical Afghan Abhog and Sanchari section) in faster tempo (drut tintal) for the second half of the recording. From 2:10 until the end he’s basically just playing one phrase, full of rhythmic variations. At this point from the tabla we can only distinguish some loud strikes, but we get the feeling that they work nicely with each other.

Interestingly, while the compositions within this track have a stronger, more complex Hindustani feeling to them, they are mostly presented with rhythmic variations, a distinctive feature of the Afghan style, and without paltas (melodic variations). He really is playing it so elegantly, the flight of a bird. In the drut part from 1:50, he is playing some typical “parandkari” or stroke pattern variations of a high pitch drone string within the composition. Nowadays, this string is raised above the others on the bridge of the rubab to be singled out easily, which wasn’t yet the case at the time of Qurban Ali.

The rubab has one well known legend who replaced Qurban Ali at the radio orchestra upon his untimely passing, the unmatched Ustad Mohammad Omar who is credited with many innovations of the instrument, and its advancement into classical music. Yet, in this recording one may recognize the most distinctive features of Ustad Mohammad Omar’s school shining already, with high-class compositions subtly elaborated, the fine ornaments and flowing rhythmical variations…

One of the aspects I find the most admirable is the mastery of dynamics, clearly discernible through the noise (powerful accentuated strokes or qamchin (horsewhip!), followed by soft passages) which was also a distinctive feature of Ustad Mohammad Omar’s aesthetics. The rubab is known as the “lion of instruments,” and Qurban Ali superbly knew how to make it roar.

There are very few vintage rubab recordings out there, and this present treasure opens a sonorous new window in time on the history of rubab, amazingly demonstrating how developed it was already a hundred years ago, by the time of Qurban Ali. As someone passionate about the instrument, words can’t describe the emotions elicited upon listening to it.

Qurban Ali. Photo from Dr. Enayatullah Shahrani’s Music in Afghanistan.

Between this recording session in June 1926 through the late 1950s, when Radio Kabul began issuing 78s via the Soviet recording industry (see this earlier post), recording of Afghan music was only sporadic, and often simply nonexistent.

In April of 1928, Mirza Nazar Khan, an amateur musician and diplomat based in Paris, made a handful of recordings in London after having been flown there on behalf of the Secretary to the Amir of Afghanistan (then Amanullah Khan, who was traveling throughout Europe at the time). These were unaccompanied recordings. They were first pressed in the UK and then repressed in 1930 in India for distribution in the region.

In July of 1928, Ustad Miran Bakhsh recorded five discs worth of Afghan selections with his ensemble, in Lucknow. One year later, he recorded another five discs in Lahore, although those later discs were not issued until 1932 for some reason.

Julien Thiennot, on his excellent website, has noted the presence of several additional Afghan performances on 78. Firstly, a disc by Akram Khan, who recorded at least once for the Afghan market in the same series as Bakhsh’s. Secondly, an additional disc from ca. 1933 by Qasem Afghan (as “Ustad Qasim Khan”) containing a topical piece about the assassination of the King of Afghanistan, Mohammad Nadir Shah. In late 1946, HMV apparently issued three 78s from, I believe, the soundtrack to Afghanistan’s first fim, “Ishq wa Dosti” (“Love and Friendship”) which was produced by an Indian film company based in Lahore known as Huma Films. Further, there was also Ustad Muhammad Hussein Khan “Sarahang” of Kabul, who recorded at least one disc for Indian HMV in the 1950s (in Hindi).

From the early 1930s until after World War II – the years when major labels had drastically reduced their recording expeditions in many parts of the world due to the Depression and the War – there appear to have been two independent labels issuing Afghan music on a semi-regular basis. In part this is likely due to the fact that they were located in Peshawar, in what is now Pakistan. These were the Banga-Phone label, run by the Frontier Trading Company, and the Gulshan label, run by Bajaj & Company. At the time, Peshawar was the capital of the “North-West Frontier Province,” once a province of British India. The region (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) bordering Afghanistan is ethnically Pashtun, which is also the majority ethnic group of Afghanistan (“Afghan” used to be a synonym for Pashtun or Pathan) and its culture and history are inseparable with that of the country. Both Banga-Phone and Gulshan issued discs that were classified as Persian, Afghani, and Multani, as well as Kashmiri and Gurmukhi. These discs are not common. After World War II, the Indian branch of the Gramophone Company acquired the catalogs of these two labels, and reissued a group of their better-known selections in 1949. They are all extremely rare today.

It could be that other discs exist on smaller labels or within the larger repertoires by major labels, we just don’t know yet. It was common, for example, for early Afghan performers to have their discs listed as “Persian” on the record labels themselves, but they actually appear as “Afghan” in catalogs, therefore there are likely discrepancies here and there, and additional Afghan recordings were probably produced during this time.

In the meantime, Qurban Ali from June of 1926.

Listen/Download:

Qurban Ali – Raag Asavari

Many thanks to Mathieu Clavel and the Michael Kinnear Collection.

Discographic notes

Label: Gramophone Company

Issue Number: P 7558

Coupling Number: 9-17901

Matrix Number: BL 2077

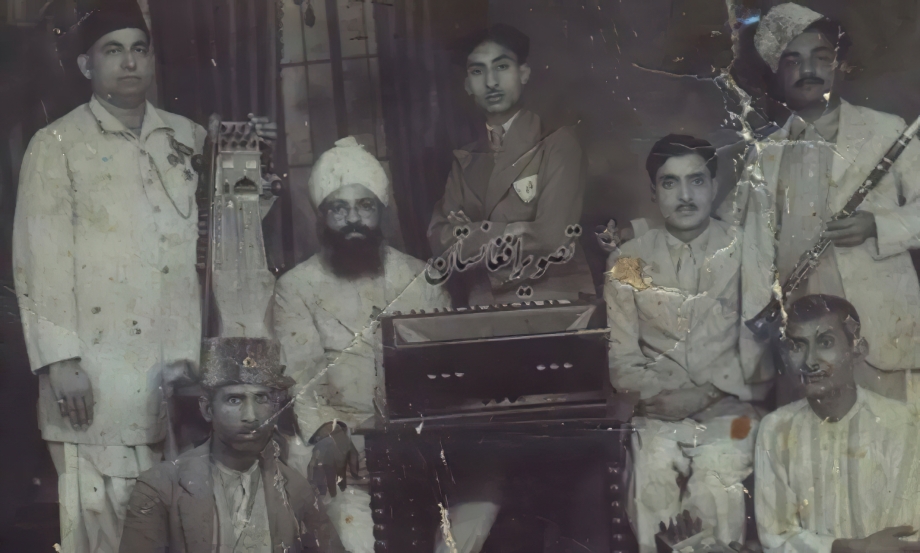

The “Ali Orchestra” – probably a young Qurban Ali, center (undated).