Sometimes one piece isn’t quite enough; it’s fun to compare, especially within a given time frame. I arbitrarily chose the year 1927 to focus on five particularly graceful taksims and instrumental improvisations within the modal framework of Turkish classical music. Many such discs were recorded and there are others I could have grabbed off of the shelf. This is just a representative drop in a bucket and are performances that I believe have not been reissued…or reissued with decent sound quality. I would definitely recommend digging further and a good place to start would be To Scratch Your Heart: Early Recordings from Istanbul, which contains additional exquisite taksims, including some from our chosen year…

Mesut Cemil had the distinction of being the son of the great Tanburi Cemil Bey (1873-1916), whom many consider to be the most important Ottoman classical performer and composer during the early recorded era. The sometimes irascible and occasionally alcoholic Tanburi Cemil Bey was not only a multi-instrumentalist, but he also revitalized the Turkish art-music solo, or taksim. He also recorded an abundance of discs in the earliest era of recording, well-circulated and revered for years (though very difficult to find in clean condition, today).

Could Mesut ever live up to his father’s revered position? Born in 1902, he studied Western classical music in Turkey as well as in Germany, while also studying tanbur first with his father and Refik Fersan (aka “Refik Bey”), a tanbur composer and student of his father. Eventually he ended up at the Darülelhan conservatory. In 1927, he’d begun working for Istanbul Radio and around October of that year, he made his first records for Columbia, including this one. This piece is a sirto – a dance piece that is also used in Turkish classical music – in the Şehnâz makam.

The long-necked Turkish tanbur (also tambur, tambour, etc) has seven strings, though early examples used eight strings in four courses. Mesut Cemil eventually had a long career both in conservatories and with urban radio orchestras. He represented Turkey at the famed 1932 Congress of Arabic Music in Cairo, and apparently discovered regional performer Âşık Veysel. He retired from music in 1955 and died in 1963.

The engineer for these original recordings must have chosen a large room with a tall ceiling, which greatly enhances their quality and mood. Some performances from these 1927 Columbia sessions were later issued for the Turkish-American market, dubbed from clean copies (as in, not from original metal masters, as they must have been unavailable) and issued on a similar, maroon label.

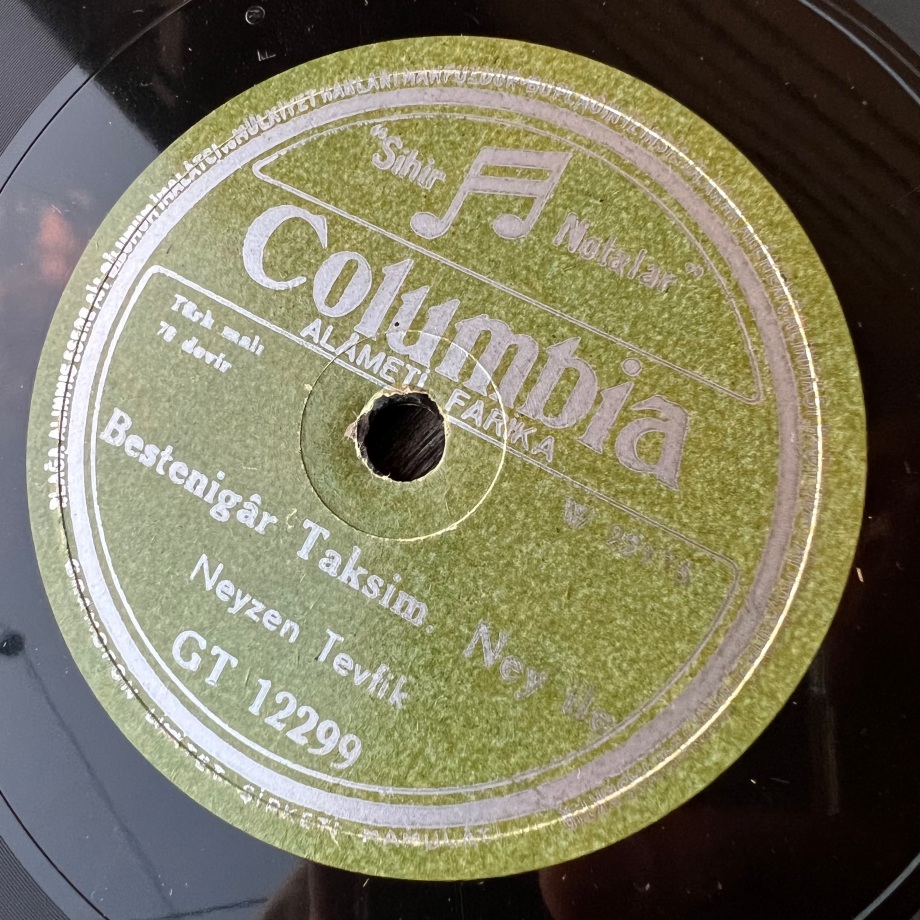

Another masterful performance from those same 1927 Columbia sessions is by the enigmatic poet who went by the name Neyzen Tevfik. He was born Tevfik Kolaylı in Bodrum in southwestern Turkey, in 1879. By the early 20th century he was a practicing Bektashi dervish. Despite being a member of the Sufi order, he is known for having a radical, unusual and sometimes contradictory life and lifestyle. Over the course of his career he wrote satirical and vulgar verse that railed against injustices and condemned autocracy. He was a staunch Kemalist, as well as a wandering vagabond, spending most of his career as a transient, living out of inns, occasionally being thrown in jail or institutionalized, and nursing a serious alcohol problem.

Biographies on him tend to emphasize those aspects of his life, but it also happens that he was a beautiful ney player, as captured here. The ney is an end-blown flute made of cane, and another important instrument in Turkish classical music. According to sources, Neyzen learned his craft in Urla on the Izmir Bay. His career on record was lengthy, recording taksims on the instrument for the Lyrophon label as early as the first decade of the 20th century. He died in 1953.

(Note for maniacs: it never ceases to amaze me the difficult-to-read color combinations that 78 record labels often used. In this case: silver lettering on green background, which makes a centered photo or a straightforward scan virtually unreadable.)

Neyzen Tevfik – Bestenigâr Taksim

Mustafa Sunar (also known as Moustafa Bey and Mousta Bey) was born in 1881 and while primarily a violin performer, it’s his rebab discs that may be his most notable. The rebab is a spike fiddle that is bowed and like many instruments, its origins are vague; there are rebab types across Asia and documented for centuries. What is relevant, however, is that while the bowed rebab was popular in Turkish classical music up to the 18th century, it fell out of fashion with the introduction of the violin. Thus, it was not as well-documented on disc compared to the violin, oud, and tanbur, and as such represents an older era of music.

This piece was recorded September 18, 1927 in Istanbul by the Gramophone Company; a taksim in the Evcârâ mode (transliterated as “Evidj Arrah” on the disc). This was a significant recording session; almost 300 matrices were made, or the equivalent of about 150 discs, by engineer Edward Fowler, right after a session in Cairo. Mustafa Sunar recorded three discs at this session.

Sunar was involved with various Turkish music conservatories and taught many students, perhaps most notably the popular singer Safiye Ayla. He died in 1961.

Eyyubî Mustafa Sunar – Evcârâ Taksim

The oud player known as İbrahim Efendi was born Avram Levi to a Jewish family in Aleppo, in 1872. He apparently learned oud from a young age, spending time in other major cities in the Ottoman Empire such as Damascus and Cairo (which gave him his name prefix: Mısırlı), before eventually settling in Istanbul.

It’s unclear precisely how many discs he made. He is often confused with a vocalist active at the same time, Hanende İbrahim Efendi, and the dates listed for his life are varied. Although he also recorded for Odeon, this piece is from the only disc he recorded during the same autumn 1927 session for Columbia featured above. He died in 1933.

Mısırlı İbrahim Efendi – Mâhûr Taksim

Aleko Bacanos’ career seems to have been somewhat obscured by his well-known younger brother, Yorgo, a highly regarded oud player who recorded for many labels himself. Aleko’s specialty was the kemençe; that is, the classical kemençe or kemenche, sometimes known as the Politiki lyra, an important instrument both in Turkish classical music but also in popular music and rebetiko played by Greeks in Izmir. Frequently referred to as “pear-shaped,” it’s a small, bowed lute played on the knee or between the knees.

Born in the Istanbul suburb of Silivri, Aleko’s earliest documented recordings were for the important early independent label of Istanbul, Orfeon, run by the Blumenthal brothers. He later recorded for Odeon multiple times during the acoustic and electric eras. For Columbia in 1927, he recorded several duet performances with his brother. This piece was made for the Gramophone Company on September 18, 1927, where, just after Mustafa Sunar had performed on the rebab, he cut six taksims. This piece is in the Sabâ makam.

This selection could continue. At the same Gramophone Company session in September of ’27, apart from Aleko Bacanos and Mustafa Sunar, several other giants of Turkish instrumental art music made records: Refik Fersan recorded tanbur taksims, Neşet Bey recorded multiple oud solos, Neyzen Tevfik was brought back for ney taksims, Artaki Candan cut six solos on the kanun. The same goes for the Columbia sessions that began just as the GramCo sessions were ending, in late September and October of that year. Apart from whom we’ve already discussed, Fuad Efendi performed taksims on the tanbur, Mustafa Sunar again appeared on rebab, Kanuni Ahmet soloed, and even Zurnazen Ibrahim cut taksims on the zurna. I believe these tracks will help add to the conversation.

Discographic details

Columbia 12660, mx 22213

Columbia GT 12299, mx 22175

HMV AX 422, 7-219324, mx BF 1308

Columbia 12307, mx 22147

HMV AX 497, 7-219350, mx BF 1300

Thanks to Gokhan Aya and Hugo Strötbaum!