The year 1930 was an extremely active one for multinational record companies. The situation in East Africa was no exception. Paul Vernon in his terrific Feast of East article has written about this scramble, but we can also now improve on some of the details. What is “East Africa” anyway? Today, at its broadest definition, it runs from Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa to the southern border of present-day Mozambique, including all the island nations and dependencies. In 1930, at least as far as record companies were concerned, “East Africa” was more narrowly defined (though it would expand). The three major players in this sprawling footrace to sell records and influence markets were those that have been written about time and again: The Gramophone Company, based in England; the Columbia Graphophone Company, also based in England (and a separate entity from Columbia in the US, though there were ties and agreements between them, just as there were between the Gramophone Company and Victor), and Odeon, based in Germany. Other labels, such as Pathé, made interesting but less-significant attempts to record East African musicians during this time frame, and likely didn’t have the wherewithal to send engineers on such a long journey (in Pathé’s case, they sent musicians from East Africa to Paris, via Marseilles, for one session).

Records were already in urban areas of East Africa – but none featured local music. The Gramophone Company gave the region over to their Mumbai (Bombay) branch, and had a presence in shops by 1926, with a profitable business selling mostly Indian records. In early 1928, they shifted focus to recording the music of the region, and in March of that year they sent Zanzibari singer Siti binti Saad and the musicians in her troupe to record in Mumbai, where they cut the equivalent of 49 discs. Copies were pressed in India at the Gramophone pressing plant. Siti became a star, and the company ended up selling nearly 41,000 copies of those discs. That must have been considered superb (though all are exceedingly rare, today). So, the company continued to record an additional 80 or so discs by Zanzibari performers across two more sessions – another in March 1929, and one in April 1930 – all made by company engineers that were based in India at that time, like Robert Beckett and Arthur Twine.

It was Zanzibar or nothing for the Gramophone Company; they didn’t expand their recording sphere in East Africa until the late 1930s. Nor did they expand their recorded repertoire, as what was recorded by GramCo during these sessions was exclusively taarab music. This is an important music of coastal Kenya and Zanzibar, sung in Swahili, deeply influenced by Egyptian music, the music of the Persian Gulf, and India. To some extent, we can say that GramCo felt that this was the style of music that would sell to people in those coastal regions – and they were right. However, it was obviously not the only type of music that existed in the area. At the time, Swahili was not quite the lingua franca that it is today, so one could surmise that recording only one style of music was also a conscious choice. In fact, it was: the Gramophone Company’s field agent in a 1931 report said as much, suggesting that as “the Swahilis become more civilised their music will absorb more and more Arabic music”; he also suggested that the “language of the smaller tribes will die out and be replaced by Swahili.” Without getting into the loaded content of those statements or the background of the person who made them, let’s just say that neither of those statements exactly came true.

GramCo’s final session in this run, in 1930, was considered an economic failure. This was in part due to musician infighting that produced a less than satisfactory session, overall depression in the trade itself, a business situation that prevented dealers from acquiring new machines or returning their dead stocks, and last but certainly not least: competition from other labels.

I’ve written before about these Gramophone Company sessions and posted an example. However, here’s an extremely rare side from the ill-fated sessions of 1930 that a friend brought back from a trip to Zanzibar years ago (if I recall correctly, it was hanging on a café wall):

Miss Peponi binti Abubakar – Na Mshangao Na Nyingi Fikira, Pt 1

Columbia saw an opportunity and they arrived in East Africa a little late in the game, in early to mid-1930. They also didn’t appear to take significant risk. They, too, primarily recorded Zanzibari musicians and taarab music – in fact, they recorded many of the same musicians that recorded for the Gramophone Company. However, Columbia sent engineers to record onsite in Zanzibar, which was a first for the island, Columbia, and the entire industry. Apparently under the auspices of a shipping company named Samuel Baker & Co., the Columbia engineers also recorded in Dar-es-Salaam – another first for recording history. While they didn’t record much in Dar, Columbia can be lauded for recording the first commercial 78s of ngoma music and music by the King’s African Rifles (KAR) band. Combined, these two sessions yielded about 62 discs.

I’ve posted an unusual example from these sessions in the past. Here’s an additional track that’s a good representation of taarab music from those sessions by Subeit bin Ambar (whose taxim I included here):

Subeit bin Ambar – Nimeiweka Nadhiri, Pt 2

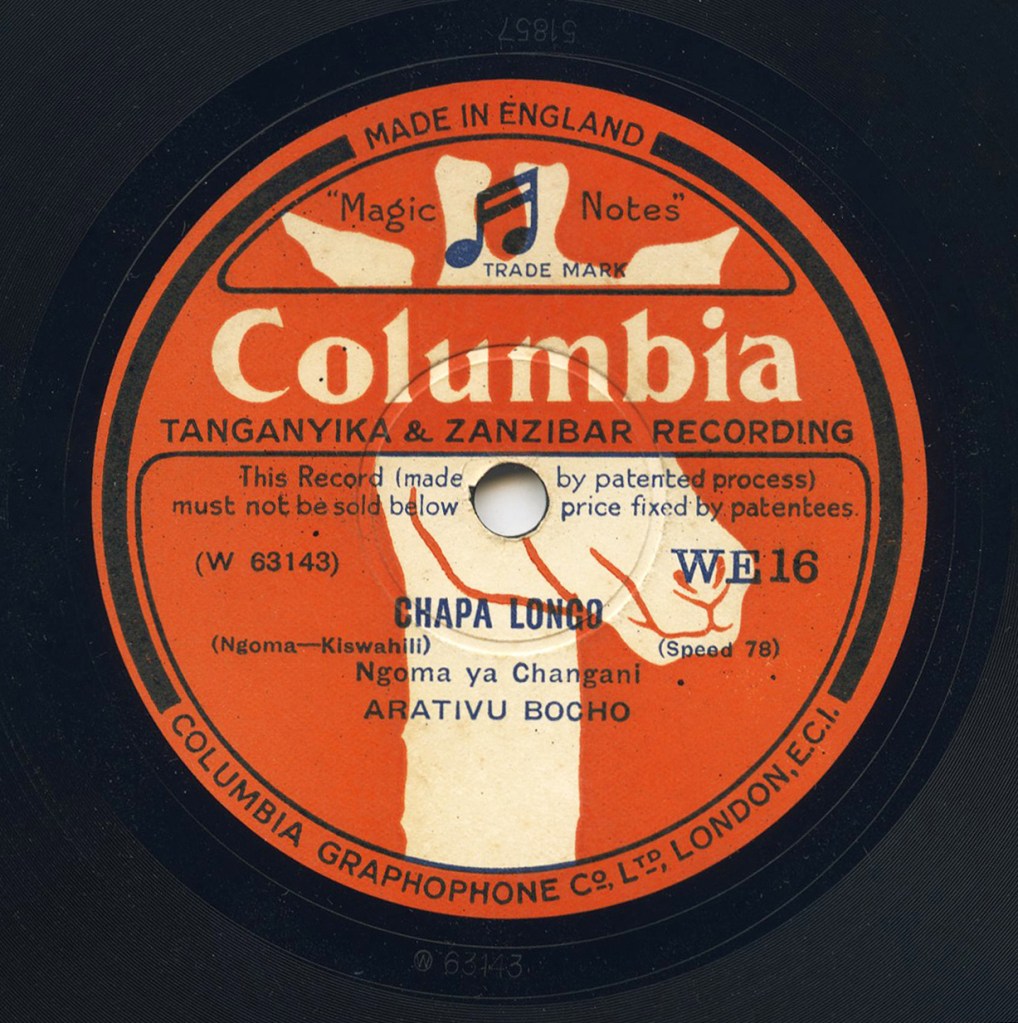

Additionally, here’s one of the scant recordings from Dar-es-Salaam, from that same recording expedition, featuring ngoma music of Tanganyika. (Another appears here.) The artist is credited as Arativu Bocho and the music as “Ngoma ya Changani.”

Who were these Columbia engineers in East Africa in early to mid-1930? It seems that the ones who recorded in Zanzibar and Dar-es-Salaam were not the same as the two – Horace Frank Chown (1900-1981) and Gustave Cook (1908-1993) – that were in Cape Town and Johannesburg in May-June of 1930, just a short while later, as there is documentation of the latter two leaving Southampton in early May and arriving in Cape Town. However, it could have been the same engineer – Wilhelm “Willy” Starkmann (1906-1992) – who, with his yet-to-be identified assistant Mr. Fischer, was in Madagascar in very late 1929, recording for the French branch of Columbia. Or, maybe not. But, more on that in a minute.

Finally, there’s Odeon. The early recording industry in Germany was truly mammoth; not simply as a multinational phonograph business hub, but also as a center for pressing discs by other, local labels around the world. However, much of this history (ledgers, masters, documentation) was destroyed during World War II and thus it has been up to tireless researchers to attempt to piece together this backstory, or at least parts of it, from what remains (existing copies of discs, material in newspapers, material in archives that survived, journals and annuals both for business and the record business, marks and matrices on discs, any clue at all). Despite these valiant, ongoing efforts over decades, there remain plenty of blank spots, even when it comes to a major, competitive label like Odeon.

Odeon’s first foray into East Africa was also in early 1930. This appears to be roughly the same time that the company recorded in West Africa (in Ghana, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone – with records issued on both Odeon and Parlophon). However, Odeon bucked the trend by not recording in Zanzibar and instead they landed in Mombasa, Kenya – yet another first in recording history – cutting the equivalent of approximately 107 discs, most of which was, like the Columbia and Gramophone Company sessions, coastal taarab music.

A couple of examples exist on compilations (I included one on Opika Pende). Here’s one that has not yet been made available:

Mwana Iddi binti Juma – Pumbao, Pt 2

Immediately afterward, Heinrich Lampe, the Odeon engineer for this East African expedition, traveled to Kampala, Uganda – once again, unique for the recording industry – where, without electricity and running his equipment on batteries, he recorded the equivalent of about 30 discs, of which it seems only 23 were issued. No one would record Ugandan music commercially for another eight years or so.

In 2013, I posted an example of traditional music from this session, with generous information from the late ethnomusicologist Peter Cooke (1930-2020). I also included a religious piece from those sessions on my last release. Here is another, a canoe song – the soloist is Mundu Tesaga and he’s accompanied by the sailors of Admiral Gabunga.

What about the OTHER colonies in the region?

In this regard, Odeon was perhaps even more active than its rivals. In late 1929, we know that experienced Odeon engineer Willi Schkölziger (1894-1958) was in Madagascar. This was roughly the same time that the aforementioned Columbia engineer Willy Starkmann was in Antananarivo. Did they cross paths? The rivals must have been neck and neck. We don’t know very much about the precise dates of the Odeon Malagasy sessions as only the Columbia sessions were reported with some detail in the local press (early October through possibly as late as December 1929). Maybe this was due to string-pulling by Columbia’s local agent in town, a Madame Salvatge, but this is just conjecture.

In any case, Odeon’s Malagasy sessions were at least as fruitful as Columbia’s. Scholar Henri Lecomte wrote in 1997 that both Odeon and Columbia’s sessions were recorded in the same structure, the long ago-destroyed Théâtre Muncipal in Antananarivo, also known as the Ambatovinaky theatre. However, recently digitized newspapers suggest that the Columbia sessions were decidedly not held at the theatre and instead at a known local residence, which may cloud things a little. Whatever the case, Odeon recorded well over 120 discs of music which were advertised in 1930 in a 16-page catalog. Most of the discs featured what is known as kalon’ny fahiny, or a type of music that blended Malagasy melodies and harmonies with western operetta, usually with piano. The primary troupes that Odeon recorded (some of whom may have been mainstays at the Municipal Theatre) were Troupe Jeannette, Troupe “Renaissance” founded by Ravelomoria Wast, and Naques Rabemanantsoa’s troupe. However, Odeon also recorded Protestant hymns, comic skits, more traditional songs by central Madagascar highland Betsileo and Betsimaraka groups, as well as at least one traditional solo artist. The discs were pressed in France and had some distribution there, but mainly sold in Madagascar. The primary distributor for Odeon discs and gramophones in Antananarivo was at the Hotel Fumaroli, the new discs being sold alongside their stock of Gujarati, Chinese, and French discs.

Here is a piece from those sessions, recorded by the Troupe Renaissance, and labeled as “Rakotovao C’s famous song.” I find some reference to Rakotovao’s full name being Rakotovao Crespin.

Troupe Renaissance – Rada Midona ny Atsimo

By January of 1930, Odeon engineer Willi Schkölziger was documented as having traveled 900 kilometers from Madagascar to Saint-Denis, on Réunion island. He was there to record the very first commercial discs of the island’s local creole music, séga – a style and dance that was borne out of the local slave populations, and one that was popular on Mauritius as well. He was accompanied by an Odeon agent named Monsieur Boissonade (or “Boissonnade”) about which there seems to be nothing known. It’s possible that Boissonade was a representative of the sponsor of their Malagasy session, Compagnie Marseillaise de Madagascar, a major colonial importer that had a hand in everything from shipping to sugar processing, and for whom a brief excursion into disc distribution would barely be noticed (and as such, is barely documented).

Of the performances Schkölziger and Boissonade recorded in Saint-Denis, it seems only about 18 discs were issued in total. Most featured a singer and guitarist named Georges Fourcade (1884-1962). Today, Fourcade is revered and recognized as the first person from Réunion to record, and doubly important because he sang local music in local dialect. His career spanned decades, performing on radio, in various groups, with hotel orchestras, and for events. He also performed at the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition. His family runs a terrific scrapbook-style website that encompasses their lives.

Here’s my own transfer of one of the séga tunes* in the series performed by the “Orchestra Bourbon” – very likely this was just another moniker for the Arlanda-Fourcade ensemble. The creole orchestra backing Fourcade was led by Jules Albert Arlanda (b. 1889), whose son also became a well-known orchestra leader.

Orchestre Bourbon – Mamzelle Zizi

By January 31, 1930, both Odeon engineer and agent had left Saint-Denis. It’s mentioned in the press that they were continuing their “world tour.”

During this time frame, there’s one significant missing piece in the story of these labels and the former colonies in East Africa and the Indian Ocean: Mozambique, or Portuguese East Africa as it was known. We have documentation that Odeon recorded in Maputo (then called Lourenço Marques) and Beira, also in 1930. According to a 1931 document prepared by a Mr. Evans, a scout/agent for the Gramophone Company active in East Africa, the Odeon sessions were the only ones of their kind; “records were made of all the principal languages” and “demand has been enormous.” Apart from that we know little more, as so few copies – if any, in collector’s hands – have appeared since then and no corresponding catalog has turned up. In fact, the only available example that I know of is in an institutional archive, at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France – transferred and made available here, on their Gallica site. Although the resolution is low, Gallica’s label scan seems to suggest that the engineer’s mark in the trail-out shellac is that of Heinrich Lampe – recorded either before or after his sessions in Mombasa and Kampala.

(image courtesy of Gallica, BnF)

Recording halted everywhere in these regions due in large part to the Depression and the merges of major companies into the newfound EMI. One exception was recording of Malagasy music, which continued during the Paris Colonial Exposition in 1931, and with the French branch of Polydor in the mid-1930s. Recording in Ethiopia began in late 1935. For the rest of mainland East Africa, commercial recording was on hold until the late 1930s, after which it was again interrupted, this time by the War.

*There is a 2001 CD issued by Takamba (“patrimoine musical de l’océan Indien”), Georges Fourcade: le barde créole, that is worth searching out for translations and wonderful personal photos – if you can find a copy. (I believe my transfer here, however, is much better.)

(image courtesy of the Fourcade family website)

Discographic data:

HMV P.13415 (80-2327; BX 7313)

Columbia WE 51 (W 63170)

Columbia WE 16 (W 63143)

Odeon A 242009b (BrO 20)

Odeon A 242135b (BrO 434)

Odeon 239022 (My 83)

Odeon 239501 (Reu 4)

Great to see you back on the innertubes!

Thank you, Randall! Great to see you!

In a world where good news is increasingly thin on the ground, a new multiple entry from Excavated Shellac is such a wonderful exception! Thank you – fantastic stuff as always, and sounding so good. Listening as I type, and looking forward to taking the time to listen more. I’ve just grabbed Opika Pende off the shelf, too.

Thanks also for acknowledging the pioneering work of my old friend Paul Vernon, who died at the end of last year. Happy memories of some great listening sessions (and stories) in his back room in Mill Hill, way back when he was still a Londoner.

Ray! Thank you for keeping the faith! I really appreciate it. And I really should dedicate this entire post to Paul – maybe that’ll be my next post! (Hopefully in fewer than three years…)

A very informative article of historical events from recordings taken in East Africa in the1930’s. Thank you for including the download tracks for listening.

A few of my favourite tracks:

Troupe Renaissance – Raha Midona ny Atsimo

Orchestre Bourbon – Mamzelle Zizi

Thank you very much for taking the time!

Your latest two posts are like Xmas in August! So happy you are still sharing the fruits of your ethno-musicological labors with us.