I wanted to focus on two examples of local, almost “one-off” 78 rpm releases that feature music of the American southwest, in the states of Arizona and New Mexico.

Broadly, throughout the 78 rpm era commercial recordings that featured music of American Indian cultures and tribes mostly fell into these categories: 1) field recordings of traditional music by ethnographers that were released commercially in boxed sets, such as Indian Songs of the Southwest recorded by Santa Fe local John Candelario, Laura Boulton’s Indian Music of the Southwest issued by RCA Victor, and American Indian Music of the Sioux and Navajo on Folkways; 2) traditional music of American Indians recorded in a studio, like this one; 3) imitative recordings of imagined traditional American Indian music, such as the RCA Victor set Music of American Indians, which is dominated by tracks performed by a studio orchestra interpolating American Indian melodies; 4) recordings of a couple of “Vaudeville Indians” who may or may not have been actual Indians, such as Chief Os-Ko-Mon aka Charlie Oskomon (who likely was not Mi’kmaq or Yakama as he claimed at different times).

A major exception to all of the above was Canyon Records of Phoenix, Arizona, established in 1951 by a non-native couple named Ray and Mary Boley. The Boleys had bought a recording studio in 1948, located a few blocks from downtown Phoenix, and named the business Arizona Recording Productions. They decided that the Canyon label would be devoted to the music of American Indians, but they operated with a less-scholarly approach and, according to sources, they preferred to let the people themselves dictate what they wanted recorded. Therefore, what was on Canyon in the early days was a broad mix of traditional and non-traditional, studio and field recordings.

The reason I mention Canyon is that on November 15, 1951, the same year Canyon was established, Arizona Recording Productions recorded this disc…but it was a private pressing and not issued on Canyon. It remains the first disc of a social dance music of southwest American Indians known as waila, or sometimes chicken scratch (though waila is preferred and the latter is considered by many to be a term used only by whites). Sounding very similar to norteño music, waila music is played by the Tohono O’odham (formerly known by the exonym “Papago”) whose reservation is in the extreme south of Arizona along the Mexico border, the Akimel O’odham, whose Gila River Indian Community is just south of Phoenix, the Quechan, or Yuma, also of southern Arizona, and the Pascua Yaqui. The term “waila” stems from the Spanish “baile” and again, like norteño, it features polkas, schottishes, boleros, cumbias, waltzes, redovas, and two-steps. Adding to the mix is the fact that waila often borrows or covers norteño songs in the overall repertoire.

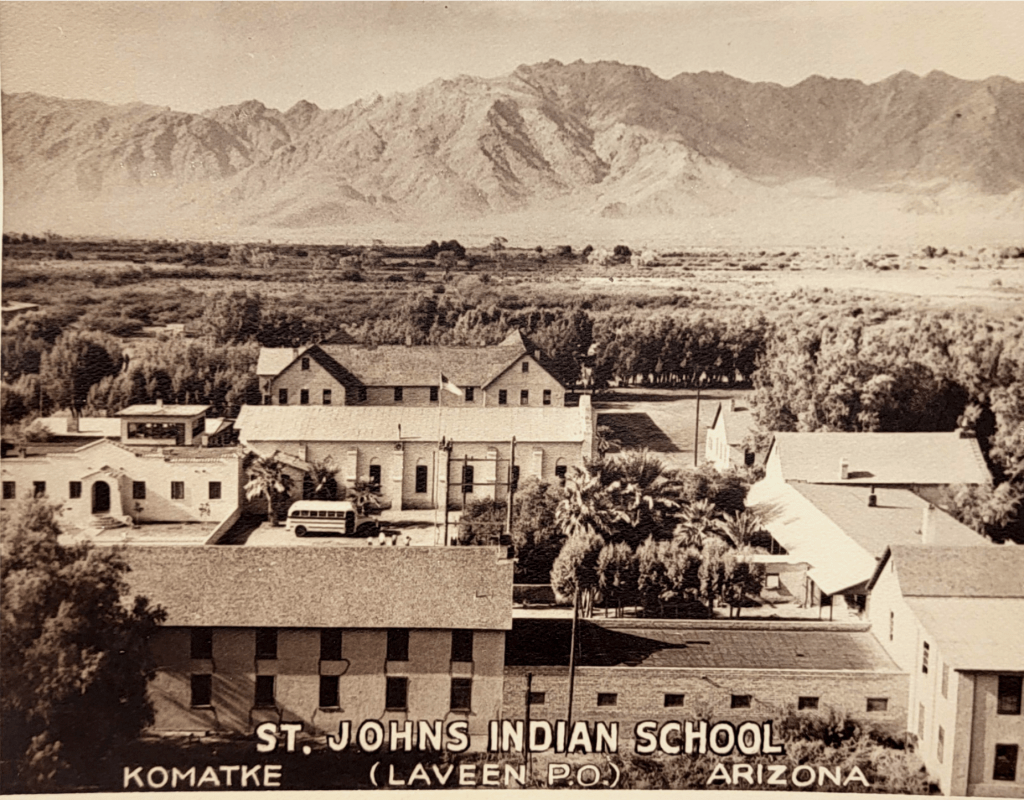

One of the best sources on the history of waila was James S. Griffith (1935-2021), who apart from writing two articles on the history of waila, also directed the Southwest Folklore Center at the University of Arizona for decades and devoted much of his scholarly pursuits to regional arts and culture in the region. Griffith, who interviewed and was friends with many waila musicians, traced the existence and development of that music in Arizona from the 1860s, when the violin and guitar has been documented as common among the Tohono O’odham, and how this instrumentation expanded to include saxophones and accordions, in part due to exposure to marching band music in the Indian boarding school system (a system of assimilation that forcibly removed Native American children to church- and government-run boarding schools).

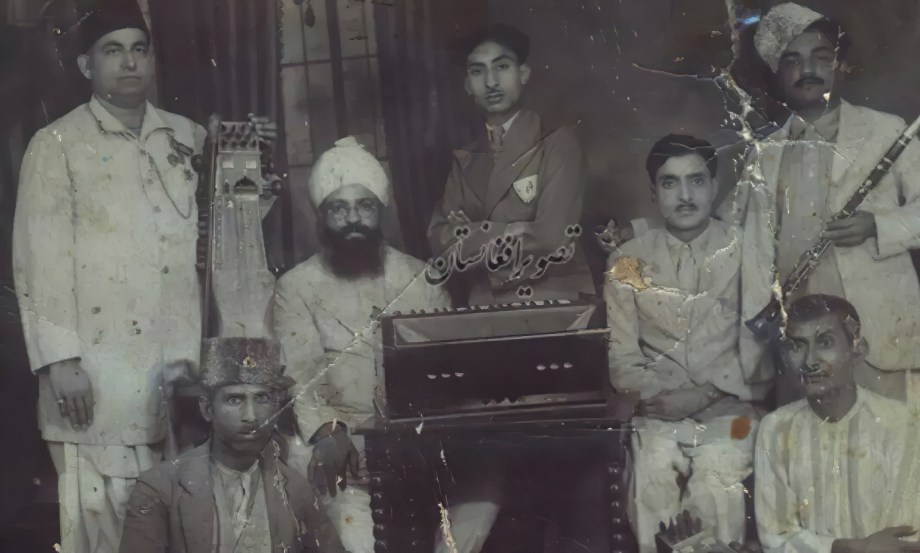

This disc has appeared on the internet before (it’s on the Internet Archive) but we can now add context. It was one of two (?) discs on the Komatke imprint (please see the comments for information on the other); it’s credited to Harry Marcus and Orchestra, though Griffith has credits for the all of the musicians: Harry Marcus (violin), Eugene Jose (violin), Augustine Lopez (guitar), Simon Felix (guitar), and Alex Augustine (guitarrón). According to Griffith, this disc was apparently recorded for “supporters of the Saint John’s Indian School” as well as for friends of the band. The school, also known as St. John’s Mission School, was founded in 1894 by a missionary named O’Connor and was a fundamental institution for many on the reservation, active until – I think – the 1990s. “Komatke” was the location of the mission and the school (the ruins of the latter are apparently still in the location, technically part of the larger town of Laveen) and is the name of a nearby mountain that is considered a source of the wind by the Akimel O’odham. Because of this, I think it’s possible that the group themselves were Akimel O’odham – however, I am hesitant to definitively state this because of the relatively common names of all of the band members and therefore the difficulty in precisely tracing them.*

This disc features two string-band versions of songs from the Mexican and Mexican-American mariachi repertoire: “Honor y Patria” and “Nos Fuimos.”

Harry Marcus and Orchestra – Honor y Patria

Harry Marcus and Orchestra – Nos Fuimos

The next item is a little different: a disc of fiddle and guitar music issued in 1949, just like it says on the label, by “Sociedad Folklórica.” As it turns out, La Sociedad Folklórica was founded in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in June of 1935, by Cleofas Martinez “Cleo” Jaramillo (1878-1956), to promote and preserve Spanish colonial folk traditions in New Mexico. After the founding of the group, Jaramillo, originally from Arroyo Hondo outside of Taos, published a Spanish cookbook and a book of Spanish fairy tales, and set about fostering events that featured dance, music, art, and traditional Spanish Colonial craft like colcha embroidery. In 1949, the membership was limited to 35 people and as far as I can tell it was, at least at that moment, run entirely by women. It still exists today.

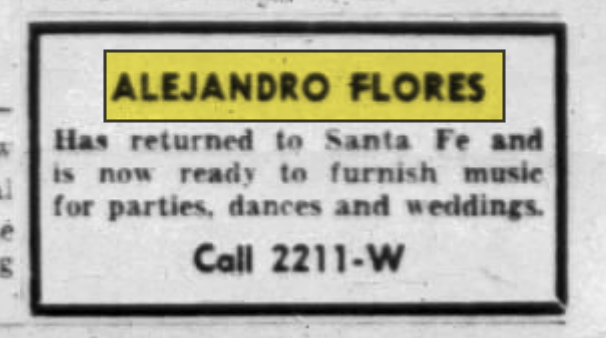

The group also produced two 12” discs with all four sides labeled as “Spanish Colonial Dance,” performed by Alejandro “Alex” Flores on violin and Ignacio Ortiz on guitar. I suspect the 12” format was preferred so the dances could be extended as long as possible, as each side is about four minutes long. The records appear to have been available only through the “music committee” of the Society and through word of mouth, and were first mentioned in late October of 1949 in the local newspaper. This is the only copy I’ve come across, and it features both an indita, a broad song descriptor that indicates a connectivity between Native Americans and “Hispanos”; and a taleán (or “talian” on the label – and there’s some indication that the song type may be Italian in origin), sometimes called a “weaving dance.” (The second disc features a cuna and a paso doble.)

Alejandro Flores was active locally in Santa Fe with his “dance orchestra” that consisted of Ortiz on mandolin, Tony G. Chavez (violin), Henry Ortega (guitar), and Evaristo Lucero (guitar). They played a variety of dances, weddings, and other events. Ignacio Ortiz had his own band and was active prior to WWII, leading a group called Los Nativos.

Why were these traditional tunes credited to “Nicholson”? I’ve no clue. The only “Nicholson” I could find associated with the Society (or the musicians) was Ernestina Delgado Nicholson, whose family had been in the region since at least the mid-19th century and whose husband was the Assistant Chief of Police. Nicholson was very active with the Society at this time. I’ve tried to contact the Society to see if they had any additional information on these recordings, but received no response.

Alex Flores and Ignacio Ortiz – Indita

Alex Flores and Ignacio Ortiz – Taleán

*There was a Harry Marcus, born ca. 1932 or 1933, who was documented on the Gila River Indian Community during the census of 1950, specifically a student at the St. John’s Mission. This is likely the leader of the group (though none of the other names listed as musicians were attending that year). There was also a Harry David Marcus (1927-1974) who was born in Sells, Arizona, on the Tohono O’odham reservation, and may have been the same person who was Vice President of the tribe in the 1950s-60s. There are several others with the same name that could potentially be the same person or conflated versions of the two (or more) Harry Marcus’.

Discographic data:

Komatke (ARP 132/3)

Sociedad Folklorica (B-6470/6471)